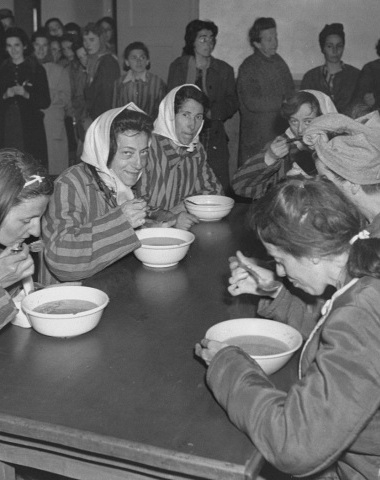

I have just returned from the Belsen concentration camp where for two hours I drove slowly about the place in a jeep with the chief doctor of Second Army. I had waited a day before going to the camp so I could be absolutely sure of the facts available. I find it hard to describe adequately the horrible things I have seen and heard, but here, unadorned, are the facts.

There are forty thousand men, women and children in the camp. German and half a dozen other nationalities, thousands of them Jews. Of this total of 40,000, 4,250 are acutely ill or are dying of virulent disease. Typhus, typhoid, diphtheria, dysentery, pneumonia and childbirth fever are rife. 25,600, three quarters of them women, are either ill through lack of food or are actually dying of starvation. In the last few months alone, 30,000 prisoners have been killed off or allowed to die.

Those are the simple, horrible facts of Belsen. But horrible as they are, they can convey little or nothing in themselves. I wish with all my heart that everyone fighting in this war, and above all those whose duty it is to direct the war from Britain and America, could have come with me through the barbed-wire fence that leads to the inner compound of the camp…

Dimbleby’s superiors at the BBC in London initially refused to believe the report. It was only when Dimbleby threatened to resign that it was broadcast, two days later on 19th April. The report brought home to the British public for the first time the horror of what had occurred at Belsen, although the broadcast version was heavily edited.